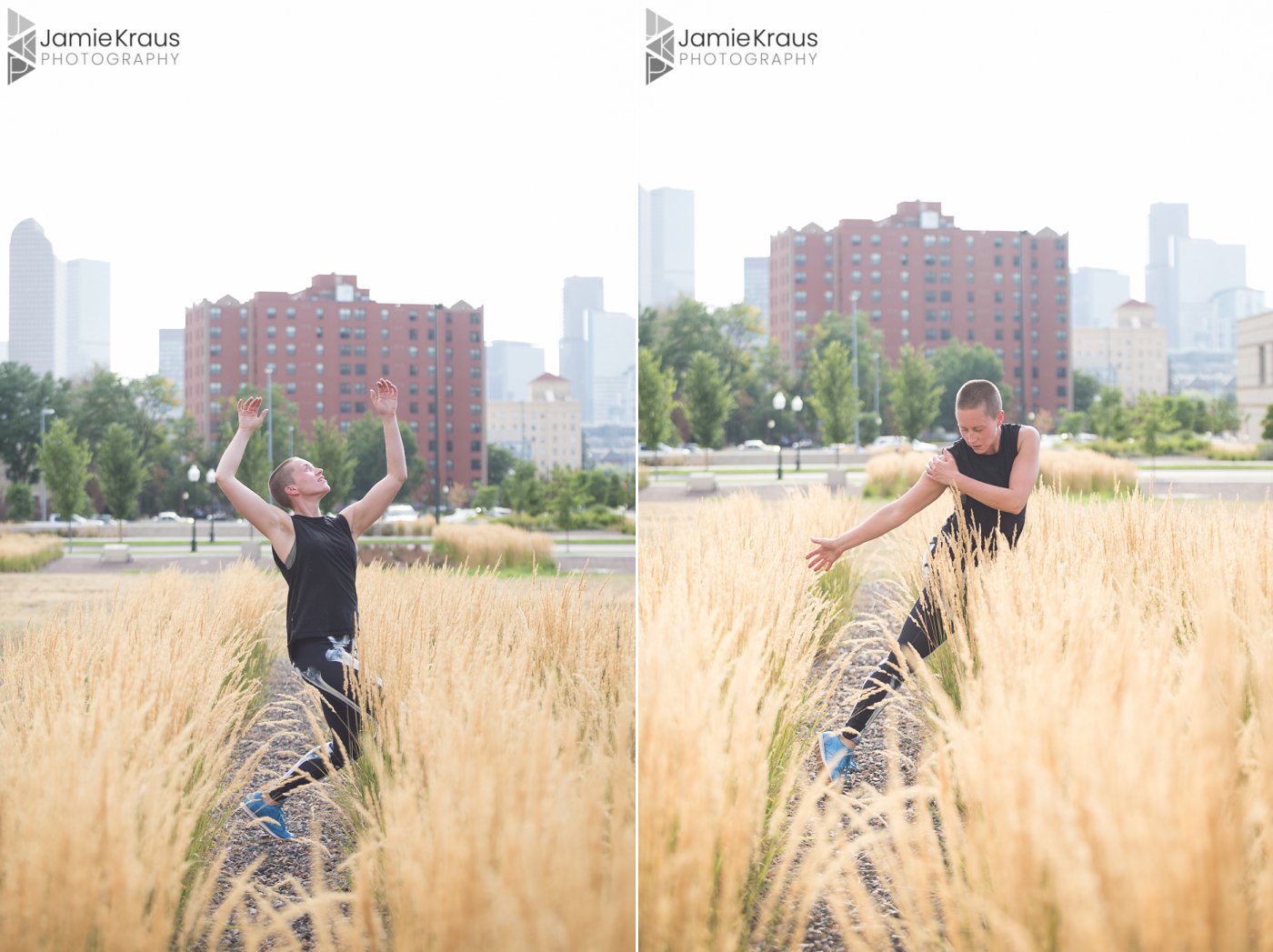

The Dance Warriors project is an artistic response to political and social issues, in collaboration with dancers across the country. This project started as my response to our changing political climate and my desire to make an impact for the better. This is my way to use Denver dance photography to raise awareness about the issues that face us today. This session features dancer Sheila Klein to raise awareness about disability justice. I was excited to explore the topics of physical disability and disability justice with Sheila because it directly relates to dance. The dance world has always had diversity problems and ablism is no exception.

Sheila and I first met years ago, at Naropa University, when I photographed a theater department performance there. They reached out to me after seeing my Dance Warriors project and wanted to be a part of it! This session got postponed for a full year. First, it was an injury, then surgery, then weather. We finally had a date set and then COVID came and pushed our plans back again. This August, we made it work and had a socially distanced session. We chose to do the session around a hospital because. Many people with disabilities spend a lot of their time at hospitals in surgery, battling with doctors to be believed, trying new treatments, and going to countless appointments. We ended the session with a much needed pop of color and optimism.

Interview with Sheila Klein on Disability Justice

Tell me a bit about yourself.

I am a White Queer person who was born in the US, a country where the privileged language is my first language. I am a human with a Master’s degree in Somatic Counseling and work both in the mental health and dance/creative fields. I identify as a performer, dance educator, and creator. I am also disabled.

I live with a triad of rare, chronic diseases: Ehlers Danlos Syndrome (EDS), which affects collagen/connective tissue and causes joint hypermobility, skin elasticity, and tissue fragility; Mast Cell Activation Syndrome (MCAS), which means my mast cell/histamine responses are out of whack; and Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS), which causes autonomic nervous system dysfunction. Because EDS, MCAS, and POTS are rare, I often am forced to receive treatment from physicians who have never heard of these conditions, doubt they are real, and have no idea how to treat a body that works like mine (and often express little interest in learning). These conditions are incurable and impact every body system all the time. In the last two years alone, I have had 13 major hip surgeries, been under general anesthesia for at least 60 hours, spent a cumulative total of 14 weeks in the hospital, and have over 30” of scars. I spent eight years of the last decade on crutches, while maintaining a career in professional dance education and performance. In my lifetime, I have learned to walk six times.

I took my first dance class at age 3, and began serious training in Western concert dance forms at age 10. I completed my BFA in Dance at the University of Michigan, which led to a decade-long career of professional dance performance in New York City. In my work, I play and experiment with dimensionality, wit, strength, critical thinking/moving, and humor. I have performed in New York, Denver and Detroit with both modern and tap dance companies including: Monica Bill Barnes and CO., J/W Motion Mix, White Void Productions (Xan Burley and Alex Springer), Amy Chavasse, Gay Delanghe, Peter Sparling, Robin Wilson, Michigan Rhythm Tap Ensemble, and Evolving Doors Dance. My original work has been presented by Triskelion Arts, Greenspace Project, Movement Research, WAXworks, and the Boulder Fringe Festival. I also teach youth in community arts centers and studios across the country.

In addition to dancing, I am a social justice counselor and specialize in work with teens/young adults, the LGBTQ community, people who have experienced acute and complex trauma, and people living with Multisystem Diseases.

Why are you passionate about disability justice?

I spent the first two decades of my life with able-bodied and able-passing privilege. I could attend social and cultural events, find housing and employment without worrying about mobility barriers; shop for food and necessary household items and be able to reach what I needed; see people of my ability level represented accurately in the media; access public transportation; trust I would not be tokenized for my ability; succeed in difficult situations without being told I was an inspiration; and choose friends and/or a partner without being seen as a disadvantage to them. I did not have to feel like my body was inferior or undesirable, or that it was something that had to be ‘fixed.’ I could speak to medical professionals and anticipate they would understand how my body works and respect my decisions about my body.

As a professional dancer, I assumed that my constant injuries were normal, and would remove braces and drop crutches to attend rehearsals and performances, knowing that my livelihood was dependent on my body looking and functioning in certain ways. Not only did I internalize the ableism that pervades U.S. American culture, I also perpetuated it (albeit unknowingly) in relationships with students, work, community, and self.

As I explore my relationship with disability advocacy/justice I am reconciling how my privilege has shaped this relationship over time. While accessibility has been important to me for decades (on the ‘I am interested in being engaged in social justice work and want to understand how to do that’ level), my own experience with disability has sharpened my awareness, deepened my sense of urgency, and clarified practical and tangible changes towards equity. For two decades I had the privilege of speculatively and academically relating with what accessibility means in real time; now, I no longer have the luxury of abstraction. I have a lot of work to do around unpacking layers of ableism in myself, my relationships, my community, and larger institutions. It is hard, inconvenient, messy, and charged – just like working with other forms of power/privilege/oppression dynamics – and, I’m in.

How has dance helped you express yourself?

Nonverbal, body-to-body communication has always made more sense to me than words. In my reality, dance and movement are more effective and adaptive tools for sharing my inner world, finding nuance, being honest, and identifying what feels most true and important. Creativity makes me feel alive, organized, and centered. As my body’s ability to move and articulate changes, I am paying more attention to subtle, detailed, and energetic forms of expression in a creative movement/dance context.

What do you think is the intersection between art and politics?

I’m not the first person to say this – nothing exists in a void. Art happens in a sociocultural and political context. Decontextualizing movement strikes me as both careless (at best) and dangerous. Some things I think about in this domain are: who has access to make art? Who gets access to see/hear/experience art? Who is considered worthy of being funded to make work? What kinds of bodies are represented in art? What kinds of bodies are exploited in art? Who decides what art is? I ask these questions not only in response to ableism, but also to racism, sexism, heteronormativity, nationalism, ageism, classism, anti-Semitism, and other power/privilege/

marginalization dynamics in the dance world. On the topic of dance and disability, specifically, I am very interested in embodied exploration of what it means to actually have an accessible, adaptable, equitable culture in dance (here, I am referring to Western concert dance, as that is the field I know well).

Representation matters – and representation does not mean tokenizing or exploiting. I have, on multiple occasions, been asked to perform during surgery recovery or use my crutches in a piece (when I am not needing them for mobility). In the same breath, these choreographers have scoffed at (or fired) me in response to a need around warm up, rehearsal pacing, or costuming. In the dance community, I constantly face the expectation that surgery recovery will be linear (it’s not), that strength or cross training will “fix” my collagen (it wont), and that the needs of the company/group/students will determine what my physical capacity will be at any given time (they don’t). I trust the good intentions of movers and creators in the dance community – and – these requests always land as exploitation and come at my cost. I can feel when I am invited to perform so a choreographer can check off an inclusivity box, maybe get more funding by having my body on stage. I sense the allure or being seen as progressive, how seductive it might be to have a public image of my disabled body associated with a company’s name. Using my body while not wanting to deal with the inconvenient or painful realities of what it means to live in that body is exploitation, not inclusivity.

So, now what? At this point, I have more questions than answers, but trust that dance communities can use the strengths we already have – creativity, sensitivity, tenacity, resilience and flexibility – to move towards an equitable, accessible, inclusive future.

Do you have something to say? Want to be a part of the Dance Warriors project? Contact me here or message me at [email protected].